The Heart of the Home (2030)

An Ethnographic Exploration with Sky Live

How do the rhythms of everyday life shape the way people interact with technology, and what could the living room of 2030 feel like? I joined Sky’s research and design teams to find out.

THE FUTURE BEGINS AT HOME

It began with a big question:

What will the “heart of the home” feel like in 2030?

Sky’s design, UX research, and product teams came together to investigate how households interact with Sky Live, an emerging product designed to bring entertainment, fitness, gaming, and video calling into a single connected experience.

The challenge wasn’t just to look at features or interfaces. We wanted to understand how real people, in real homes, live with this technology. Not in labs. Not in usability sessions. In their kitchens, living rooms, and multi-generational spaces, surrounded by distractions, responsibilities, pets, and people.

This is how I found myself co-leading an ethnographic research project, one that brought together product, UX, UI, and interaction design teams with a shared goal to observe, listen, and imagine the next chapter of connected living.

FROM DISCOVERY TO DIRECTION

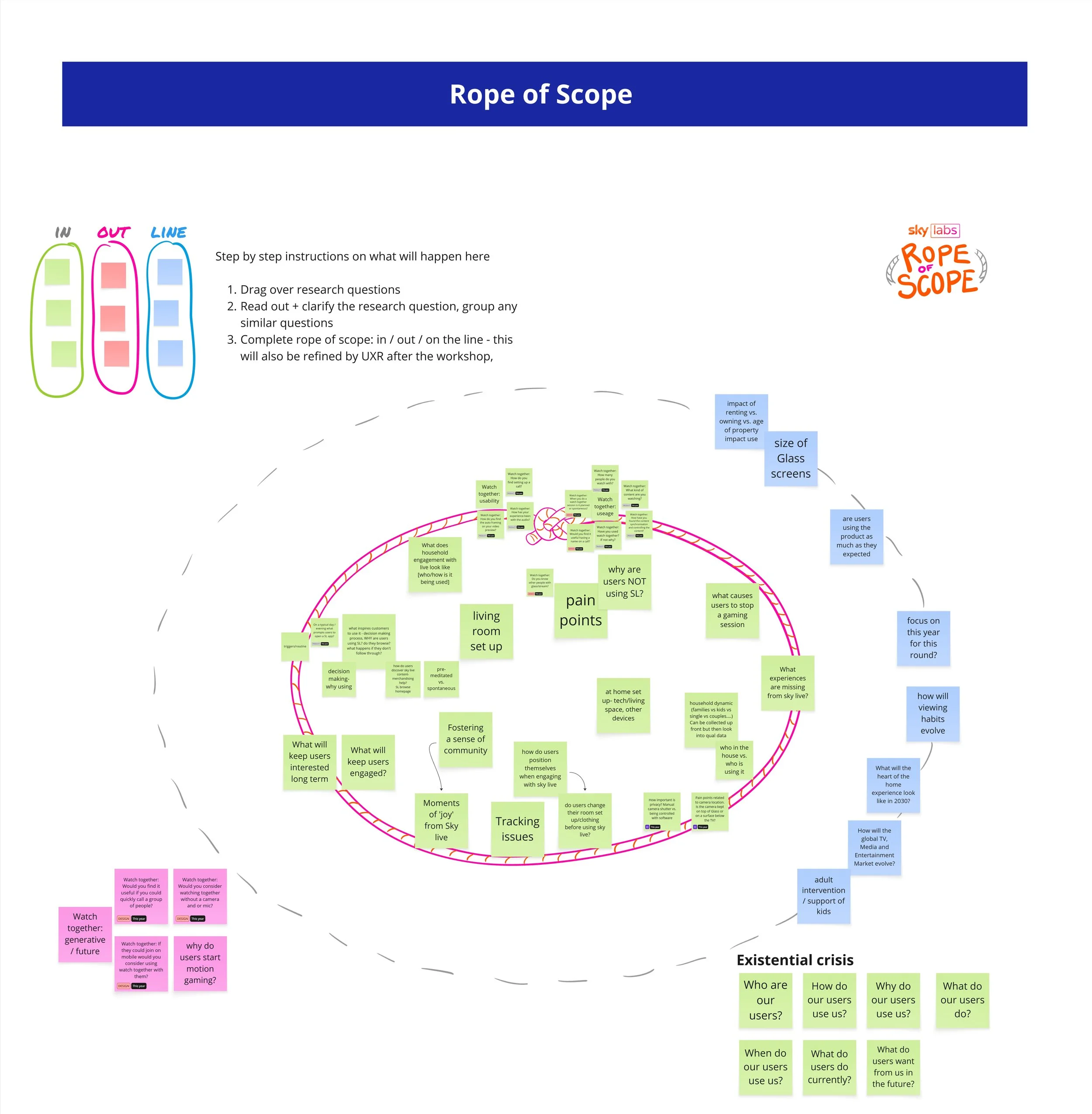

Our investigation began with a series of collaborative workshops and research deep-dives. We asked ourselves:

- How do household dynamics affect engagement with Sky Live?

- What are users actually doing when they discover new features?

- What assumptions are we carrying about usage—and which ones need to be challenged?

We studied previous research, user feedback, satisfaction metrics, and product usage data. But to go further, we needed to step into people’s homes.

I joined the team just as the project was ramping up. We aligned around ethnography as our methodology, because to design for the heart of the home, we had to be in the home. We weren’t just investigating a digital product. We were exploring how technology fits into the rituals, layout, and rhythms of daily life.

PLANNING THE ETHNOGRAPHIC SESSIONS

Together, we co-developed a wide-ranging scope, from what interrupts a gaming session, to who makes decisions in a household, to how people move through their spaces and react to unfamiliar features. Our workshops surfaced key questions about accessibility, ownership, family dynamics, motivation, and even how cultural identity and space constraints shape usage.

To truly understand what role Sky Live plays in people’s homes, we committed to ethnographic fieldwork. This method allowed us to study not just what people said, but what they did, how they moved, who they shared with, and what their tech setup actually looked like.

We recruited a wide range of Sky Glass + Sky Live customers across London, from multi-generational homes to families with kids, from renters to homeowners, and across various accessibility contexts.

Before heading into the field, I took part in a hands-on workshop where I was introduced to our participant through UserZoom survey data. I reviewed responses covering everything from their daily routines and household layout to product usage, frustrations, and motivations. Using that data, I built a detailed persona that outlined:

Who the user was living with

What their home environment was like

How they currently interacted with Sky Live

Their product goals (e.g., fitness, gaming, video calls)

Their known pain points and barriers to use

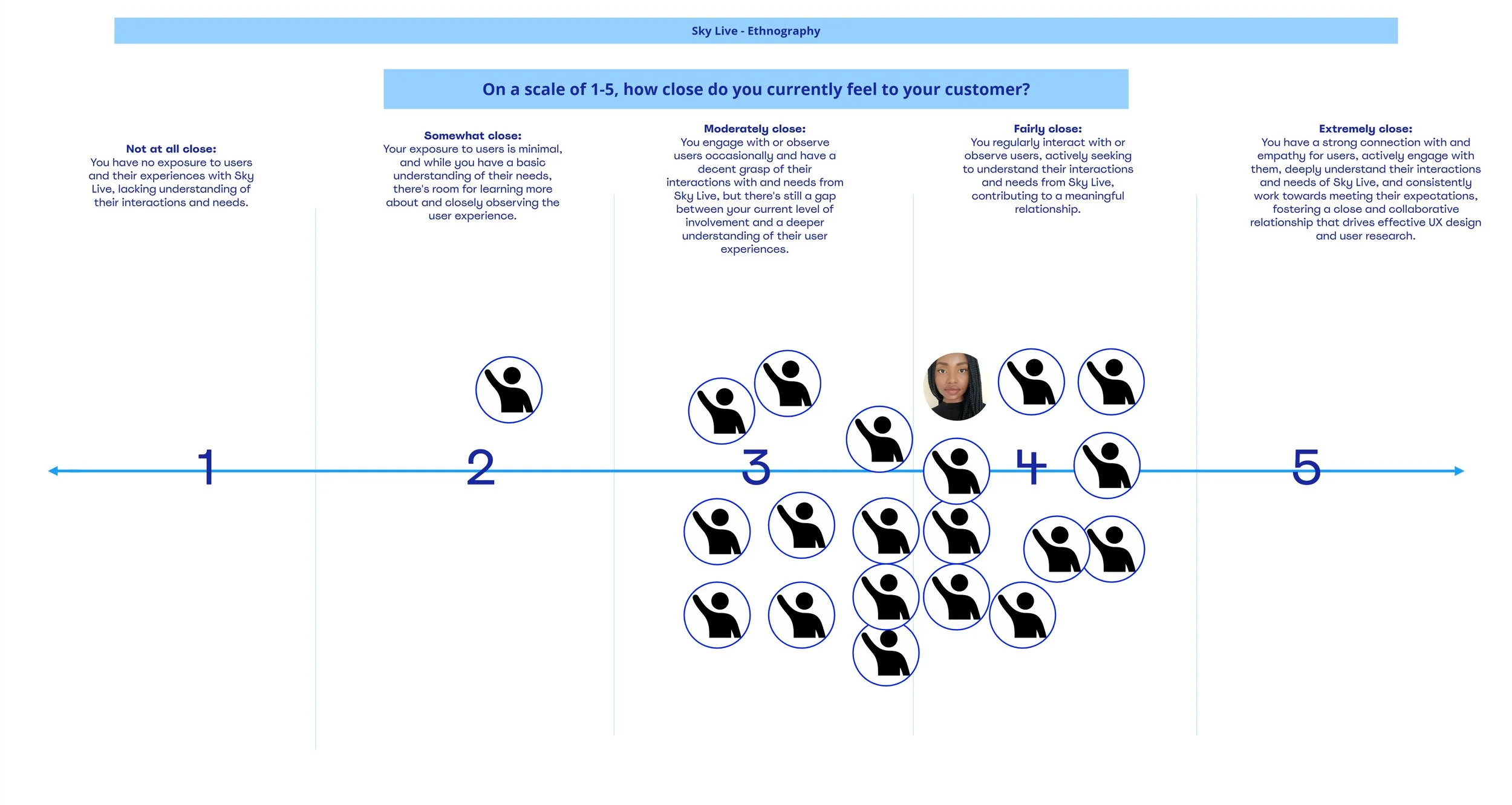

Synthesising this information helped me move beyond surface-level assumptions and begin building a mental model of the user’s world. As part of the workshop, I reflected on how close I felt to the participant. I rated myself as feeling “somewhat close”, meaning I understood the basics of their life and needs, but recognised that the real insights would come from seeing it first-hand.

ADAPTING IN REAL TIME

Originally, I was scheduled to attend a session with a young family. But the day before the field visit, my participant cancelled. Rather than sitting out, I volunteered to join another session with a new participant. It meant switching partners, adapting to a new user, and quickly realigning my role, all within a short timeframe.

It was one of those small but telling moments that reminded me how messy and human UX research can be, and how important it is to remain flexible and open.

THE FIELD VISIT: VALERIE’S STORY

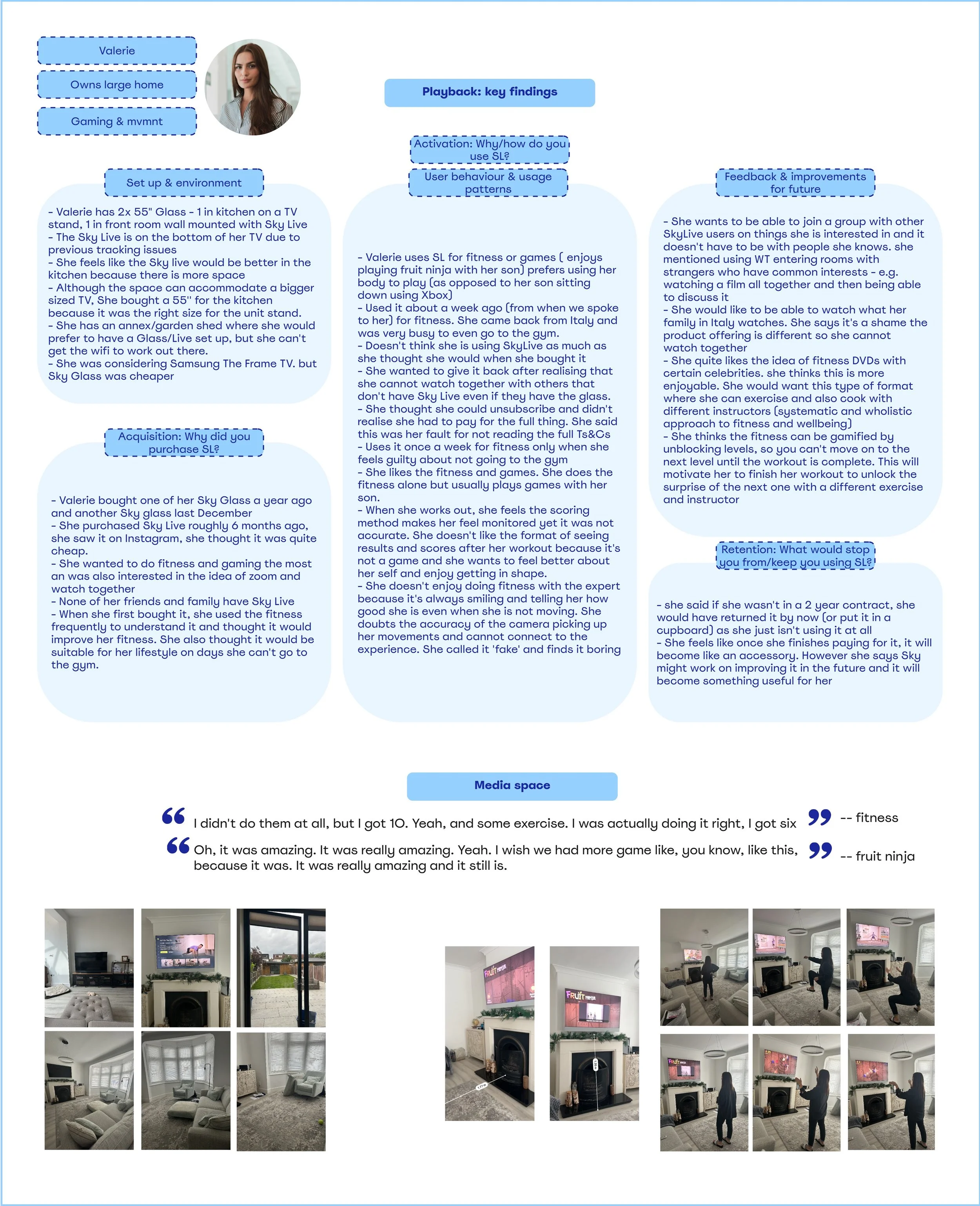

She had considered buying Samsung’s “The Frame” for its aesthetic but opted for Sky Glass because it was cheaper. This decision reflected a mix of practicality, curiosity, and convenience, which also framed her attitude toward the product.

Our participant, Valerie, is a 46-year-old general manager at an airport, living with her husband, teenage son, a friend, a cat, and a dog. She described herself as a fitness enthusiast and purchased Sky Live six months earlier after seeing it on Instagram.

Her motivations were clear, she loved the idea of interactive workouts, gaming with her son, and using features like Zoom and Watch Together to connect with others. But what unfolded in her living room was far more complex, and insightful.

Valerie had two Sky Glass TVs, one wall-mounted in the living room with Sky Live attached, and another in the kitchen. Interestingly, she felt Sky Live would be more useful in the kitchen due to better floor space, but she’d placed it in the living room due to previous tracking issues. She even expressed interest in setting up Sky Live in her garden annex, but couldn’t due to unreliable Wi-Fi.

ACTIVATION AND USE IN DAILY LIFE

Valerie initially used Sky Live regularly, especially the fitness features, which she hoped would fit around her schedule when she couldn’t make it to the gym. However, usage quickly declined.

“I use it when I feel guilty for not going to the gym. Maybe once a week.”

She and her son enjoyed playing Fruit Ninja, and she preferred movement-based games over traditional console play.

But limitations soon emerged, when speaking about her use of Sky Live. She had assumed she could use Watch Together with her family in Italy, only to find it required both parties to own Sky Live, not just Sky Glass. She hadn’t realised the full cost commitment, and joked that if she weren’t locked into a contract, the device might already be sitting in a cupboard.

Her biggest issue, though, was with the fitness experience. The scoring system felt arbitrary. She questioned the camera’s accuracy. And the upbeat, “You’re doing great!” feedback felt robotic and disingenuous.

“I didn’t do them at all, but I got 10. It’s always smiling, telling me I’m doing great, even when I’m not moving. It feels fake.”

What she wanted was something more real, more human, a workout that respected her effort, not one that gamified it for the sake of positivity.

INSIGHT INTO THE DETAILS

Valerie’s story revealed much more than product feedback. It revealed emotional friction. The technology worked, but it wasn’t connecting. It didn’t feel like it fit her life, her mood, or her motivations. She wanted progress, narrative, even surprise in her experience. She compared Sky Live unfavourably to her favourite celebrity fitness DVDs, which offered storytelling, personality, and structure.

She dreamed aloud about unlocking new instructors through completed workouts. She imagined hybrid experiences like cooking and fitness together, content with warmth and variation. She wanted to connect with others, even strangers, in interest-based rooms. And she longed for the ability to watch content with her family across borders.

“It doesn’t have to be people I know, I’d love to join others who are watching or doing the same thing.”

“Imagine finishing a workout and then cooking something together with the instructor. That would keep me coming back.”

These insights weren’t just feature requests, they were emotional needs. Valerie wanted to feel motivated, connected, and understood, and she gave us a glimpse into what a more human version of Sky Live could look like.

Being in Veronica’s home, watching her interactions, and listening to her speak so openly about her experiences helped deepen my understanding far beyond what I had imagined from her persona.

In the follow-up retrospective, we revisited the same scale we used before the session, this time reflecting on how close we now felt to our participants. I rated myself as feeling “fairly close”. It was a small but meaningful shift, one that reminded me how much more empathy you can build just by sitting in someone’s space, observing quietly, and letting their story unfold in their own words.

TURNING OBSERVATION INTO OPPORTUNITY

After the session, I synthesised my notes and presented the story of Veronica to the broader team. It became clear she wasn’t an edge case. Rather, she represented a very real type of user, curious, motivated, tech-aware, but not tech-led.

Her insights helped us uncover gaps between expectation and experience, and they inspired new ideas around community, modular content, and the emotional honesty of feedback systems.

More importantly, they reminded us that product success isn’t just about what features are possible, but about how they land in someone’s real, imperfect, everyday life.

LEARNING FROM THE PROCESS: A PROJECT RETROSPECTIVE

We regrouped for a final project retrospective workshop to reflect on what we’d learned, about our users, the research process, and ourselves. We used a simple framework:

Loved, Loathed, Longed for.

What stood out was how open and reflective the team was. We celebrated how smooth the logistics were, how powerful it was to be inside real homes, and how energising it was to present our findings live instead of reading static reports.

“We shouldn’t take this kind of research access for granted. We need to find ways to bring more teams into the homes of real users.”

We also discussed what didn’t go so smoothly, like participant cancellations, underestimated time commitments, and post-session fatigue. Writing up the results was harder than expected, and some struggled to balance this alongside their main roles.

In terms of improvements, the team suggested:

Booking backup participants to prevent lost research days

Clarifying playback timelines and deliverable expectations

Offering support on question phrasing to avoid leading or biased interviews

What I appreciated most was how solution-focused the feedback was. We weren’t just closing a project, we were opening the door to better, more scalable field research in the future.

REFLECTIONS

This project taught me the quiet power of observation. I wasn’t leading the interviews. I was supporting, capturing, holding the details. But in those details, in how a participant stood, spoke, gestured, or paused, was everything.

I learned how to adapt under pressure, how to build rapport as a guest in someone’s space, and how to work cross-functionally with researchers, designers, and product managers.

It also reminded me that design is about more than screens. It’s about context. Physical, emotional, cultural context. And sometimes, the best way to understand that is to take off your UX hat, sit down in someone’s living room, and just watch.

WHY THIS PROJECT MATTERS

This project deepened my UX practice in:

Ethnographic research & contextual inquiry

Persona building & synthesis storytelling

Adaptability in live research settings

Collaboration with multi-disciplinary teams

Human-centred design thinking grounded in real lives

And most importantly, it gave me the chance to ask:

What does “living well” with technology really mean, and how can we help design it?

THANK YOU!